50th Annual Pow Wow, Postponed until Further Notice!

The CSULB Pow Wow originally scheduled for March 14 & 15 2020 has been postponed until further notice. Come join us for the 50th Annual CSULB Pow Wow at Puvungna. The largest and oldest student sponsored event on campus, our celebration of life is attended by the CSULB American Indian community, alumni, staff, students, faculty, the general public, dancers, singers and venders who make up the over six-thousand people who attend our annual celebration of Native American Culture at “the Beach.” Held at the upper campus quad, the event is free however parking is $10 per day. To learn more about the 50th Annual Pow Wow click on this link and the links in the column to the right to see past Pow Wows at the Beach.

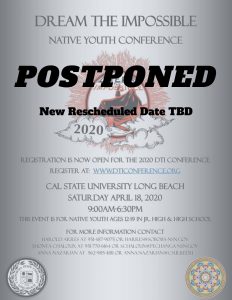

Dream the Impossible Native Youth Conference April, 2020

CSULB will host the 14th Annual Dream the Impossible Native American Youth Conference on has been postponed!

For details see: http://dticonference.org.

http://dticonference.org./

49th Annual Pow Wow

Celebrating 50 Years of American Indian Studies at CSULB.

Rain or Shine, the CSULB American Indian community, alumni, staff, students, faculty and the general public who make up the six-thousand visitors who attend our annual celebration of Native American Culture at “the Beach” this year on March 9 & 10, 2019 at the 49th Long Beach Pow Wow at Puvungna.

To learn more about the Annual Pow Wow check out the links on the right column of the AIS Main Page and the following link. Link to Pow Wow Information

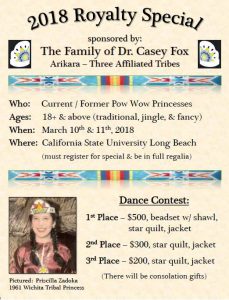

48th Annual Pow Wow Rain or Shine

Rain or Shine, the CSULB American Indian community, alumni, staff, students, faculty and the general public who make up the six-thousand visitors who attend our annual celebration of Native American Culture at “the Beach” this year on March 10 & 11, 2018 at the 49th Long Beach Pow Wow at Puvungna.

To learn more about the Annual Pow Wow check out the links on the right column of the AIS Main Page and the following link. Link to Pow Wow Information

California Indian Genocide Awareness

As part of an ongoing effort to increase awareness of the Californian Indian Genocide, the American Indian Studies Program and the American Indian Student Council sponsored several events this Fall of 2016.

The American Indian Student Council installed two public artworks to raise awareness of the California Indian Genocide on campus that was on view for the entire month of November. Link to article These artworks installed by American Indian Student Council officers, Ashley Glenesk and Miztla Aguilera with Professor Craig Stone were seen by thousands of students, faculty and staff were also featured on the CSULB webpage. Link to article

As part of Native American Month, the Native American Student Council sponsored a lecture by Benjamin Madley the author of An American Genocide: The California Indian Catastrophe 1846-1873, in conjunction with the Ethnic Studies 319 and AIS 336 courses. The presentation took place in the USU Ballrooms on Tuesday, November 8th from 2:00 to 3:15 pm, followed by a book signing. Over one-hundred and fifty students attended the lecture in conjunction with the Puvu Indigenous Cultural Sustainability Lecture Series and the Scholarly Intersections Grants from the College of Liberal Arts.

It’s time to acknowledge the genocide of California’s Indians

By Benjamin Madley

Between 1846 and 1870, California’s Indian population plunged from perhaps 150,000 to 30,000. Diseases, dislocation and starvation caused many of these deaths, but the near-annihilation of the California Indians was not the unavoidable result of two civilizations coming into contact for the first time. It was genocide, sanctioned and facilitated by California officials.

Neither the U.S. government nor the state of California has acknowledged that the California Indian catastrophe fits the two-part legal definition of genocide set forth by the United Nations Genocide Convention in 1948. According to the convention, perpetrators must first demonstrate their “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such.” Second, they must commit one of the five genocidal acts listed in the convention: “Killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

It is not an exaggeration to say that California legislators also established a state-sponsored killing machine.

California’s Legislature first convened in 1850, and one of its initial orders of business was banning all Indians from voting, barring those with “one-half of Indian blood” or more from giving evidence for or against whites in criminal cases, and denying Indians the right to serve as jurors. California legislators later banned Indians from serving as attorneys. In combination, these laws largely shut Indians out of participation in and protection by the state legal system. This amounted to a virtual grant of impunity to those who attacked them.

That same year, state legislators endorsed unfree Indian labor by legalizing white custody of Indian minors and Indian prisoner leasing. In 1860, they extended the 1850 act to legalize “indenture” of “any Indian.” These laws triggered a boom in violent kidnappings while separating men and women during peak reproductive years, both of which accelerated the decline of the California Indian population. Some Indians were treated as disposable laborers. One lawyer recalled: “Los Angeles had its slave mart [and] thousands of honest, useful people were absolutely destroyed in this way.” Between 1850 and 1870, L.A.’s Indian population fell from 3,693 to 219.

It is not an exaggeration to say that California legislators also established a state-sponsored killing machine. California governors called out or authorized no fewer than 24 state militia expeditions between 1850 and 1861, which killed at least 1,340 California Indians. State legislators also passed three bills in the 1850s that raised up to $1.51 million to fund these operations — a great deal of money at the time — for past and future anti-Indian militia operations. By demonstrating that the state would not punish Indian killers, but instead reward them, militia expeditions helped inspire vigilantes to kill at least 6,460 California Indians between 1846 and 1873.

The U.S. Army and their auxiliaries also killed at least 1,680 California Indians between 1846 and 1873. Meanwhile, in 1852, state politicians and U.S. senators stopped the establishment of permanent federal reservations in California, thus denying California Indians land while exposing them to danger.

State endorsement of genocide was only thinly veiled. In 1851, California Gov. Peter Burnett declared that “a war of extermination will continue to be waged … until the Indian race becomes extinct.” In 1852, U.S. Sen. John Weller — who became California’s governor in 1858 — went further. He told his colleagues in the Senate that California Indians “will be exterminated before the onward march of the white man,” arguing that “the interest of the white man demands their extinction.”

Beyond premeditated, systematic killings of California Indians, other acts of genocide proliferated too. Many rapes and beatings occurred, and these meet the U.N. Genocide Convention’s definition of “causing serious bodily harm” to victims on the basis of their group identity and with the intent to destroy the group. The sustained military and civilian policy of demolishing California Indian villages and their food stores while driving Indians into inhospitable mountain regions amounted to “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.” Because malnutrition and exposure predictably lowered the birthrate, some state and federal decision-makers also appear guilty of “imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.”

Finally, the state of California, slave raiders and federal officials were all involved in “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” Thousands of California Indian children suffered such forced transfers. By breaking up families and communities, forced removals constituted “imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.” In effect, the state legalized abduction and enslavement of Indian minors; slavers exploited indenture laws and federal officials prevented U.S. Army intervention to protect the victims.

The issue of genocide in California poses explosive political, economic and educational questions for the state, California’s tribes and individual California Indians. It is up to them — not academics like me — to determine the best way forward.

Will state officials tender public apologies, as Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush did in the 1980s for the relocation and internment of some 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II? Should state officials offer compensation, along the lines of the more than $1.6 billion Congress paid to 82,210 of these Japanese Americans and their heirs? Might California officials decrease or altogether eliminate their cut of California Indians’ annual gaming revenues ($7.3 billion in 2014) as a way of paying reparations? Should the state return control to California Indian communities of state lands where genocidal events took place? Should the state stop commemorating the supporters and perpetrators of this genocide, including Burnett, Kit Carson and John C. Frémont? Will the genocide against California Indians join the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust in public school curricula and public discourse?

These are crucial questions. What’s beyond doubt is that the state and the federal government should acknowledge the genocide that took place in California.

Decency demands that even long after the deaths of the victims, we preserve the truth of what befell them, so that their memory can be honored and the repetition of similar crimes deterred. Justice demands that even long after the perpetrators have vanished, we document the crimes that they and their advocates have too often concealed or denied. Finally, historical veracity demands that we acknowledge this state-sponsored catastrophe in all its varied aspects and causes, in order to better understand formative events in both California Indian and California state history.

Benjamin Madley is assistant professor of history at UCLA and the author of “An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873.”

Link to Past Genocide Awareness Efforts

Ancestors Final Journey Home

In advance of California Native American Day, California State University Long Beach held an event to officially recognize the reburial of remains and various artifacts in an area on the campus. CSULB President Jane Close Conoley expressed her honor that the school is one of the first institutions to complete a reburial on a university campus under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). The celebration included speeches and traditional Native American songs. Long Beach September 22, 2016. Photo by Brittany Murray, Press Telegram/SCNG

CSULB becomes the first university to support a reburial of Native American ancestral remains on a campus.

“As an alumnus of California State University Long Beach and first student to graduate with an American Indian Studies degree from CSULB, I am proud of my school for listening to our Indian Nation representatives and Indian Studies faculty and students for giving appropriate rest and protection to these ancestors so that they may fulfill their journey. This has been the only time that a University has given of its campus for repatriation and establishes a strong precedent for other institutions who have made their footprint on top of, and obtained research dollars from, Native American graves. I know that this repatriation has gone a long way to repair relations and create a strong bond between Indian Nations in Southern California and the University,” said Shannon Keller O’Loughlin (Choctaw), Alumnus and former member of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Review Committee, lawyer, and Chief of Staff of the National Indian Gaming Commission. (Ms. O’Loughlin’s views and opinions are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Indian Gaming Commission.)

Link to Press Telegram Article

Ancestors Final Journey Home

In 1953, Long Beach State Anthropology Professor, Dr. Ethel Ewing, was called to investigate a report of human remains and artifacts unearthed during the construction of the Los Altos Shopping Center. What was encountered was a cemetery linked to the ancient village site of Puvungna, the spiritual center of the Gabrieleno-Tongva tribe. What was once the expansive traditional land-base of the tribe, became economic fodder for land developer, L. S. Whaley, and his Los Altos Realty, Inc. in a post WWII urban setting. This scenario has repeated itself throughout the decades, as Southern California Indian cemeteries and sacred sites have been disturbed and destroyed as a result of uncontrolled development.

Universities, and other public institutions, have become repositories of Native American ancestral remains that were abandoned by a system that participated in salvage excavations and failed attempts to maintain the dignity of human remains while being used for research. After generations of ancestors physically confined within institutions, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 [1]implemented a change that would return the dignity and integrity to these individuals/ancestors.

In 1994, the ancestors of the Village of Puvungna were repatriated under the Native American Graves and Protection Act of 1990. Since then, there has been a concerted effort by culturally affiliated tribes, including the Gabrieleno/Tongva and Juaneno/Acjachemen, to rebury their ancestors on campus, the closest location to their original resting place.

It has been a long drawn out process, often a conflicting and unfriendly setting, through multiple CSULB presidents, finally finding resolution with the support of CSU Chancellor Tim White, interim President Don Para, Provost David Dowell, and with the support of CSULB President Jane Conoley, and her current administration who have embraced the reburial.

On July 23, 2016, the reburial ceremony was quietly held on campus, members of ten local tribes, including the Gabrieleno/Tongva, the Juaneno/ Acjachemen, and members of the Chumash tribe took an active part in the reburial ceremony. The ceremony took place on campus at a site collectively chosen by a collaboration between university and tribal representatives. After osteological investigation, the final count of individuals whose remains have been reburied increased from the original 21 to representing about 100 ancestors.

CSULB takes position as the first academic institution to complete a Native American reburial under NAGPRA on their campus. However, this reburial was not the first on campus. Prior to NAGPRA, in 1990, an ancestor was reburied on campus after it was unearthed during the installation of a sprinkler system. AIS Program Director, Craig Stone was a student at CSULB at that time and attended the meeting with then CSULB President Steven Horn in 1978 which resulted in the first reburial of an ancestor at CSULB in 1979.

The recent major reburial process was incorporated into the educational setting across campus linking eleven courses in an unprecedented three-year collaboration. The courses included are from American Indian Studies, Anthropology, Art, Design, Environmental Science and Policy and Recreation and Leisure Studies at CSULB with the consistent support of Vice President, David Salazar. The excavation was overseen by Dr. Sachiko Sakai, Cogstone Resource Management, Cindi Alvitre and supported by the CSULB Physical Planning/Facilities Management and their Staff.

A major role for many aspects of the reburial was performed by current NAGPRA Coordinator, Cindi Alvitre, who coordinated and oversaw the preparation of the ancestors for reburial by students, tribal community members, and scientists to correct a historical wrong.

Louis Robles, Jr., the Chairman of the Committee on Native American Burial Remains and Cultural Repatriation at CSULB is the son of the late Lillian Robles who along with Xoxa Hunut, Jimmy Alvitre, Jimmy Castillo, Anthony Morales, Rebcecca Robles, Cindi Alvitre, Rhonda Robles, Dwight Manuel, Georgiana Sanchez, Jan Sampson, Eugene Ryule, Jerry De La Moira, Craig Stone, Deborah Sanchez, Gloria Arellanes and many others, were actively involved in this on-going effort to rebury the ancestors.

It is with great pride that we announce the completion of this effort to rebury the ancestors at CSULB on the eve of the 2016 celebration of California Native American Day.

[1] https://www.nps.gov/nagpra/ The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was enacted on November 16, 1990, to address the rights of lineal descendants, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations to Native American culture. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was enacted on November 16, 1990, to address the rights of lineal descendants, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations to Native American cultural items, including human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. The Act assigned implementation responsibilities to the Secretary of the Interior.

We Are Changing — New Partnerships in AIS

We Are Changing — New Partnerships in AIS

Link to Daily 49er article about new Minor

The American Indian Studies Program has recently established partnerships in three colleges to offer a revised minor in Native American Cultures for students in majors leading to professions that impact the lives of American Indian People.

These partnerships began in the Fall of 2014 with a focus on Museum Studies/CRM, Anthropology, Social Work, Art History and Film as the first phase of changes to American Indian Studies and now include partnerships with nineteen departments and programs. In the Fall of 2016 we will expand our partnerships with the School of Art and with the Department of History with cross-listed courses in American Indian History and Contemporary Indigenous Arts in the United States and American Territories.

In the Spring of 2016 students in American Studies, Anthropology, Art, Art History, Comparative World Literature, English, Film & Electronic Arts, Geography, History, Human Development, Journalism, Kinesiology, Museum Studies, Music, Philosophy, Political Science, Recreation & Leisure Studies, Social Work, and Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies will be able to enhance their studies with the new AIS Minor and and graduate on time.

Students interested in learning more about the AIS Minor in Native American Cultures Link to New 15 Unit Minor or our new Certificate in American Indian and Indigenous Studies Link to 21 Unit Certificate are encouraged to contact the Director of the AIS Program, Craig Stone at: cstone@csulb.edu

Current AIS Minors should contact AIS Advising in PH 1, Room 104 to see if the new 15 unit Minor will help them to graduate in less time. 562.985.7804

American Indian Graduation Celebration

American Indian Graduates gathered with their families to feast and celebrate their achievements on Saturday, May 14th from 6-9 p.m. in the University Student Union Ballrooms. American Indian Graduates were honored with song, prayer, gifts and awards in the USU Ballrooms with over one hundred and thirty in attendance. Student, Alumni, Memorial, Prayer, Round Dance, Tongva and Kumeyaay songs were sung during the evening to celebrate these achievements and to honor and remember those who have gone before us.

American Indian Graduates gathered with their families to feast and celebrate their achievements on Saturday, May 14th from 6-9 p.m. in the University Student Union Ballrooms. American Indian Graduates were honored with song, prayer, gifts and awards in the USU Ballrooms with over one hundred and thirty in attendance. Student, Alumni, Memorial, Prayer, Round Dance, Tongva and Kumeyaay songs were sung during the evening to celebrate these achievements and to honor and remember those who have gone before us.

Congratulations to our American Indian Graduates and we welcome you as our newest CSULB American Indian Alumni.

Image of Kathy Leonard who earned an Masters Degree in Education.

Below are photos by Mitzla Aguilera of the celebration.

Indian Hill Releases CD Live from Long Beach

Indian Hill releases new cd, Indian Hill : Live from Long Beach

Recorded live at the CSULB 46th Annual Pow Wow at Puvungna in March of 2016. The album consists of fourteen songs recorded when Indian Hill was our host Northern Drum. You can purchase a physical cd copy from Blood River Entertainment (or from any of the singers). Link to purchase CD

Digital Downloads can be purchased at the following links.

iTunes link Amazon link Google Music link Cdbaby link

Forty-Six Years of American Indian Studies at CSULB

Forty-Six Years of American Indian Studies at CSULB

Founded in 1968, the American Indian Studies Program celebrate forty-six years as an independent program at Cal State Long Beach. Located on the ancient village site of Puvungna and listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a Sacred Site and the birthplace of an Indigenous Religion, CSULB is referred to as “the Beach” in reference to our location on the Pacific Ocean and as “Cal State Puvungna” in acknowledgement of the significance of our location at a sacred site that continues to be used for prayer and ceremony today. Serving one of the largest Urban American Indian populations in the United States, our urban intertribal American Indian traditions are celebrated during the second weekend of March at the largest and one of the oldest student sponsored event at Cal State Long Beach, the annual CSULB Pow-Wow. Now forty-five years old, over six thousand students, staff, faculty, alumni and community members attend our annual celebration of life that acknowledges the contributions of American Indians at Cal State Long Beach. The theme for this year’s celebration is “growing in two worlds” and refers to the ability of achieving balance in life. Special thanks to Pam Muro who translated the theme and has provided a link on how to say this in Tongva, “Growing in two Worlds”.

Founded in 1968, the American Indian Studies Program celebrate forty-six years as an independent program at Cal State Long Beach. Located on the ancient village site of Puvungna and listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a Sacred Site and the birthplace of an Indigenous Religion, CSULB is referred to as “the Beach” in reference to our location on the Pacific Ocean and as “Cal State Puvungna” in acknowledgement of the significance of our location at a sacred site that continues to be used for prayer and ceremony today. Serving one of the largest Urban American Indian populations in the United States, our urban intertribal American Indian traditions are celebrated during the second weekend of March at the largest and one of the oldest student sponsored event at Cal State Long Beach, the annual CSULB Pow-Wow. Now forty-five years old, over six thousand students, staff, faculty, alumni and community members attend our annual celebration of life that acknowledges the contributions of American Indians at Cal State Long Beach. The theme for this year’s celebration is “growing in two worlds” and refers to the ability of achieving balance in life. Special thanks to Pam Muro who translated the theme and has provided a link on how to say this in Tongva, “Growing in two Worlds”.