SP22 PHIL620

Seminar in History of Philosophy (PHIL620)

Topic: Animal Consciousness in the Early Modern Period

Dr. Larry Nolan

Tuesdays · 7:00pm–9:45pm · LA1–304

In this course we will analyze and evaluate philosophical arguments for and against the existence of animal consciousness from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries. Philosophers treated in the course will include such major figures as Montaigne, Descartes, Locke, Malebranche, Leibniz, and Hume, as well as several minor figures, including Henry More, John Norris, and Pierre Bayle. We will attempt to understand their positions and motivations within the context of their larger philosophical systems and the scientific advances of the day. We will also be interested in identifying their opponents among ancient and medieval thinkers.

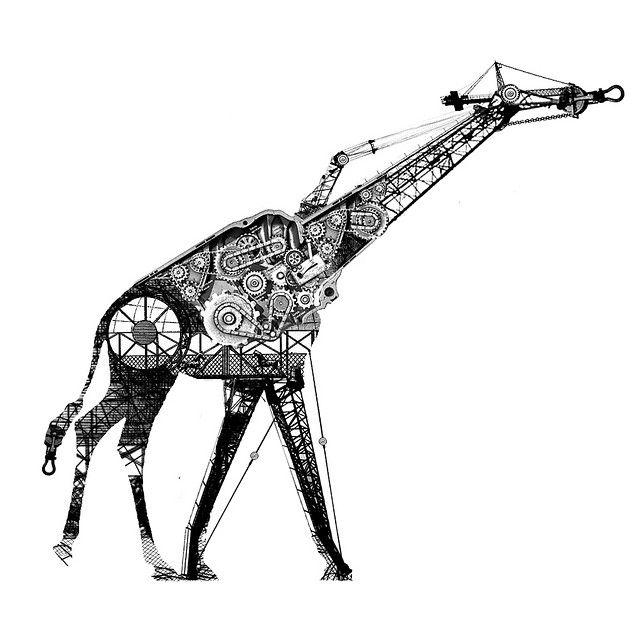

Everyone tutored in philosophy is aware of Descartes’s infamous beast-machine doctrine, according to which nonhuman animals are mere automata, devoid of sense and reason. Today, with our deeper knowledge of animal physiology, genetics, and ethology, such a view seems as quaint as it is easy to refute. If one steps on a dog’s paw, it cries out. What could be more obvious than that it is evincing pain and is thus conscious? Descartes and many of his followers who uphold this doctrine are of course well aware of such empirical evidence, but regard it as indecisive and trumped by metaphysical, epistemological, and theological considerations. The arguments they develop are extremely provocative and ingenious, and worthy of rigorous analysis, which they have not yet received. Some of their demonstrations appeal to considerations of linguistic competence, others to ontological parsimony (or Ockham’s Razor). Still other arguments invoke thoughts about the nature of God, especially concerning divine wisdom, benevolence, and justice. In fact, there are clear parallels with arguments in the philosophy of religion pertaining to the problem of evil. The danger of any demonstration for the conclusion that animals are mere automata is that it might apply equally to human beings, thus entailing that they lack immortal souls and free will.

Not all (or even most) philosophers in the period hold a negative view of animal consciousness. For example, the French Renaissance essayist, Montaigne, believed that animals are more sagacious than humans. Locke maintained that the difference between human and animal consciousness is merely one of degree; and others, such as Hume, agreed.

Some early modern figures use the debate over animal consciousness as an occasion for exploring their own philosophical obsessions. Locke, for example, exploited it to argue for his thinking-matter hypothesis, according to which thought is a property added by God to some parts of matter—a form of materialism in the philosophy of the mind. One of the main reasons that some philosophers in the period denied that animals think or feel is the concern that it would commit them to the existence of animal souls, which in turn entails that beasts are immortal in the same way as human beings. Leibniz, however, held that everything in the universe, including animals, is an immaterial substance or soul-like entity. He avoided the theologically disastrous conclusion of granting animals immortality by proposing instead that their souls are merely indestructible, which implies that, unlike humans, they lack self-consciousness and moral agency. He thought we are thus able to grant animals consciousness while still distinguishing their suite of mental capacities from that of human minds. Like many philosophers going back to Aristotle, Leibniz contrasted humans with animals in order to make substantive claims about human nature.

Students in the course will be required to attend class regularly, contribute frequently to discussion, deliver live presentations, and write a term paper or a series of shorter papers.