1918

Studio Publicity

1918

Effects of the Great War (1914-1918): Hollywood’s Supremacy

The Great War had interrupted filmmaking across the globe, harming fatally Balboa’s relationship with both its European distributors, Pathé and Bishop, Pessers, and Co., Ltd. The war also made film stock expensive because the same chemicals were used to fabricate explosives needed for the war effort. Consequently, the movie industry entered a slump around the world with many prestigious companies folding, though major California studios would rule supreme in the emerging Hollywood, to which Balboa’s own success had contributed in creating during Hollywood’s emergence between 1913 and 1918. As early as 1916, Hollywood appeared to be overtaking both Eastern (U.S.) and European production centers that had dominated the movie scene before the war years. On the other hand, the Horkheimers’ enterprise would not survive 1918, facing bankruptcy for its flawed distribution methods and due to events beyond the Horkheimers’ control, explained below as “acts of God” that closed the Horkheimer chapter during Hollywood’s emergence.

Above all, good relations between producers and distributors had become essential by 1917, during this critical turning point in global film history. In fact, between 1916 and 1946, all facets of filmmaking would become Southern California’s major industry and contribute to the state’s population growth, the state’s population exploding from a meager 1.5 million inhabitants in 1907 to over 5 million by 1930, thanks in large part to Hollywood’s successful movie industry.

American Preeminence after 1918

At war’s end with the signing of the Armistice, November 11, 1918, many Europeans could not return to the lives they had led before. Some countries ceased to exist, including many of the grandest empires on European soil–the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Russian Empire, the Prussian Empire (the second German Reich), and the Ottoman Empire, the conflagration of war ushering in much turmoil and confusion with unstable governments, changing boundaries, and exhausted national economies. Starting anew seemed impossible even for the winners who remained intact, such as the British and French empires. For example, before the war, France enjoyed the enviable position of being the number one producer of some of the industrial age’s most prestigious engines—automobiles, airplanes, and motion pictures. As a consequence of the war, such technological preeminence in key industries would shift from war-weary Europe to the United States of America.

Balboa’s Fatal Flaw: Film Production & Distribution Kept Separate

For Balboa, there were several fatal blows: losing Pathé as a distributor, the devastating Influenza of 1918, and eventually the Oil Strike of 1921, the latter having completely altered the economy and face of Long Beach, transforming it into an industrial port and petrolium producing center rather than a seaside resort and entertainment mecca. Above all, several studios, including Balboa, would fail to fathom the necessary marriage between producers and distributors to assure their mutual success and longevity. In retrospect, the most successful studios by the end of the Great War ran their own theater chains and handled their own distribution, providing a steady distribution system for their product.

The Break-Up Between Balboa and Pathé

Ever vigilant about cost and quality control, Pathé, in its efforts to deal with market loss during the Great War, had asked the Horkheimers as early as 1916 to slow down production. While the strength of the Horkheimers Brothers might have been their diversified and innovative marketing approaches, including both French and British distribution, in the end, the brothers made a fatal error in turning a deaf ear to Pathé’s request to slow down production.

Later, when Pathé refused to release Balboa productions, the Horkheimers and their creditors had to figure out how to hold Balboa’s assets together. However, before the Balboa-Pathé break-up, the Horkheimers had been following the advice of Pathé’s Felix Malitz, that is, keeping film production and distribution separate:

(Drawn from Balboa Films, pp. 148-152): Felix Malitz, formerly the vice-president and general manager of Pathé Frères and Pathé Exchange, made this observation in Moving Picture World (July 06, 1917),“Producing and Distributing Should be Strictly Separated,” claiming that production costs, passed on to the consumers at the movie theatres, could be reduced and efficiency heightened if producers tried never to distribute their own films. The Horkheimers had followed this rule of thumb, in having associated themselves early with two major distributors, Fox and Pathé, back in 1914; however, the marriage between Pathé and Balboa failed by 1918, during a slump in the post-war market, forcing the Horkheimers to lose the very strong partnership that Malitz advocated to avoid unnecessary costs and delays in production and distribution.

The Irony–1918, A Promising Year for Balboa

January 23: Daily Telegram, “Biggest Year in Balboa’s History Is Present Plan–Two More Working Units Added“: The closing of two of the largest studios in Los Angeles yesterday (Triangle & Universal), attributed to fuel conditions, will in no way affect the Balboa studio, of this city, according to H. M. Horkheimer, its president and general manager. “Instread of curtailing its output,” Mr. Horkheimer said today, “Balboa is getting ready to put on two more companies–that is working units, next week (Kathleen Clifford Co. & Anita King Co.). And we plan to increase our activities materially, in the very near future, as 1918 promises to be the biggest year in Balboa’s history. The fuel shortage does not affect Balboa in the least, because we do not require it. Balboa operates on the abundant sunshine of Southern California. When that fails, we are provided with a light studio. So far as I know, the Federal Fuel Administration has issued no orders to California studios to close down.”

Concerning the closing of the Triangle and Universal plants, two of the largest in the industry, Mr. Horkheimer said that he understood that it was largely due to the fact that they had been working ahead and had enough completed productions on hand to run them for a while. “In view of this fact,” he continued, “it simply amounts to their taking up some slack. We have none at Balboa and the demand for our pictures is increasing so steadily that two we will keep right on working. As I see it, film competition is gradually setting down to a battle of the ‘survival of the fittest.’

Balboa’s Fatal Mantra–“Keeping Production & Distribution Separate”

“January 23 (continued): Daily Telegram, “Biggest Year in Balboa’s History Is Present Plan–Two More Working Units Added“: The studios closing are what is known as ‘program organizations’. They have long been opposing the contest of the exhibitors for booking–that is the right to buy wherever they saw fit. Independent manufacturers have been getting stronger right along, as a result of this contest, for they realize that the exhibitors are the backbone of the industry. For a long while, the program companies had a death grip on the picture industry; but it is being relaxed, wherefore the day of the independent producer is getting brighter, all the time. In four years, Balboa has from the humblest sort of beginning grown into the largest actually independent film producing plant in the trade. Never having sold any stock, it is a private enterprise and run entirely as such. As much cannot be said for some of the other studios, which have many shareholders. Trouble has been brewing for them, for quite a while. It may be that their day of reckoning is at hand. I am glad to be able to say for Balboa, however, that it looks hopefully to the future and a long life. In the near future, we will begin the production of another big serial. Close? I should say not. Balboa is just beginning to get busy, since we have the facilities to do really big things now.”

Long Beach Still Attracting the Best: Charlie Chaplin at Balboa

February 1918: The future still looked bright for the Horkheimers. Arbuckle‘s company was filming a series of movies at Balboa and had plenty of big plans ahead in Long Beach. Charlie Chaplin was photographed clowning around on Arbuckle’s set during one of his three visits to Balboa. Marc Wanamaker reported that Chaplin was interest in doing his own productions, carefully eyeing the Balboa facilities.

Balboa Studio–Left: H. M. Horkheimer and Charlie Chaplin; Right: left to right–Charlie Chaplin at camera; Lou Anger, manager for Arbuckle; H. M. Horkheimer of Balboa; Buster Keaton. Charlie Chaplin visited the Balboa Studios on three separate occasions.

February 23: The Moving Picture World: Paul Powell was hired by Balboa to make a serial, Who Is ‘Number One’? for Paramount written by Katherine Nelson

Balboa to Launch a New Star–Mona Lisa

February 27: The Daily Telegram, “New Star in Filmdom Whose Resemblance to Famed Painting Is Remarkable,” 3:1: Another Mona Lisa has been discovered, and in Long Beach! No copy of the original painting this time; but a young woman whose resemblance to the famous beauty, immortalized by Leonardo de Vinci’s celebrated canvas, is almost uncanny. And stranger still, the likeness is not merely a matter of chance but inherited; for genealogical research has revealed the fact that this latterday Mona Lisa is lineally descended from the medieval Giorondos of Florence.

[…] H. M. Horkheimer, a leading motion picture producer, has been combing the world of fair women, in search of one who would measure up to his ideal for a contemplated film production. To this end, upwards of a thousand applicants have been passed on in recent years. Many have been beautiful and possessed of charm. Yet, each lacked something which prevented her even approximating the standard set.

About the time he was beginning to despair of ever finding the desired type, Mr. Horkheimer had a caller.

“Mona Lisa!” he greeted her.

“Why call me that?” she smiled.

“Because of the striking resemblance you bear to the famous painting. It is unmistakable–your eyes, the smile, that face! Ever had any stage experience?”

“Some,” she admitted, “and now I want a chance to work before the camera.”

That was easily arranged. At the try-out, she brought to view exceptional photographic qualities and showed the sort of dramatic fire which should rapidly make her a favorite with screen connoisseurs.

[…] Mona Lisa’s first screen appearance will be in an emotional drama of seven reels. The piece is one Mr. Horkheimer has been waiting years to do, while seeking the right player for the stellar role. In Mona Lisa, he is sure she has been found, at last. The play, from which the film version has been adapted, is to be presented on Broadway’s speaking stage about the same time the motion picture is released.

Paul Powell, a Griffith director, who is filming the piece, predicts that Mona Lisa will prove one of the greatest finds in the history of the screen. It has been a long time since a new film star of the first magnitude was discovered. Mary Pickford, Clara Kimball Young, Mae Marsh–all hark back several years, to the beginning of the feature photoplay. Meanwhile numerous actresses have vainly sought to displace them in the public’s favor, or to win a place for themselves in their class.

Comes now Mona Lisa, with her subtle smile and soft eyes, seeking a following of her own. Endowed with youth, beauty and artistry, she starts unhandicapped and should readily win the coveted niche, if her grip proves anything like that of Leonardo da Vinci’s wonderful art treasure.

March 3: The Moving Picture World: Mona Lisa and Wilfred Lucas to appear together for Balboa, directed by Paul Powell.

A Robust Enterprise at the Brink

After the Horkheimers submitted, March 26, 1918, a statement of their assets and liabilities to a meeting of their creditors, Variety printed that very statement a few days later, April 5, 1918, showing a robust enterprise:

| ASSETS | AMOUNTS |

|---|---|

| Real estate and buildings | $105, 292.54 |

| Plus investment | $2,610.64 |

| Subtotal | $107,903.18 |

| Less mortgage | -$14,900.00 |

| Subtotal | $93,003.18 |

| Plus equipment | $112,551.63 |

| Plus supplies | $10,771.60 |

| Plus contract rights, scenarios, etc. | $55,318.35 |

| Plus pictures | $174,032.02 |

| Plus accounts receivable | $3,269.92 |

| Plus petty cash | $100.14 |

| Total assets | $449,046.84 |

| LIABILITIES | AMOUNTS |

| Bank loans, etc. | $48,729.44 |

| Bank overdraft | $5,811.88 |

| Salaries payable | $57,959.79 |

| Trust funds | $44,032.90 |

| Trade and miscellaneous accounts | $63,433.09 |

| Total Liabilities | $219,967.70 |

| Capital | $83,350.00 |

| Total of Liabilities & Capital | $303,317.70 |

| Surplus | $145,729.14 |

| $449,046.84 |

Still Hoping for a Turn-Around

March 26: Variety, “Balboa Plant To Be Operated By A Committee Of Creditors,” The total assets of the Balboa Amusement Producing Company were reported to be $449,046.84 and the liabilities $219,967.70. The same article claims that the company would not be placed in bankruptcy, with nearly 200 creditors in attendance at the meeting. Most of the creditors rejected the idea of bankruptcy, deciding that the movie plant should be handled by a committee of creditors, consisting of three representatives of the banks at Long Beach, along with three representatives of general creditors and three labor claimants, or employees of the company. The article concluded:

“The Balboa studio was attached last week by the Wholesalers’ Board of Trade, to satisfy debts and the Labor Commission present claims for salaries which have been incurred since the Horkheimers began operations. According to a statement made by the company, the liabilities are around $20,000, with assets consisting of studio property, completed films, etc., $40,000. The plant will continue to run in order to complete unfinished pictures, but outside executives will be brought in” (49).

As late as May 29, 1918, trade journals expected Balboa would rebound, reporting that the Balboa Amusement Corporation would begin production of a series to be released in 5-reel parts for ten weeks, a new venture about which film circles were buzzing. The serial was supposed to total 50 reels, to be the longest of its kind ever offered. The new serial involved the latest discovery by the Horkheimers, as they promoted their nascent star—Mona Lisa, who bore a striking resemblance to Leonardo daVinci’s original. The Horkheimers, however, would not bridge the widening gap eroding during the slump in the market, in the aftermath of the most horrendous war that had ever been known to man, involving too the dismantling of the greatest trading partner of the United States—Europe. The Great War had made Pathé more cautious, in a war-torn economy, and when Pathé withdrew his financial backing, the punch forced the Horkheimers to bow out in the months to come, abandoning their successful movie business, the preeminent industry of Southern California that the Horkheimers had helped forge during their meteoric rise to fame and glory.

Los Angeles Wholesalers Board of Trade

April: H. M. and Elwood assigned their studio to the Los Angeles Wholesalers Board of Trade for liquidation. By agreement, the Balboa Amusement Producing Company would stay in operation under the new trustees. Although H. M. Horkheimer always hoped to make a comeback, publicly announcing his intentions in 1923, neither he nor his brother produced another movie after 1918. Defending his honor at an embarrasing and painful moment, H. M. was quoted in Moving Picture World:

“The attachment of the studios on Monday, by the Los Angeles Wholesalers Board of Trade, was made at my suggestion and by which agreement was made with all of the studio’s creditors. It is a well known fact that the sales market from a sales standpoint has been upset for sometime, as a direct result of which larger producers and Balboa have been pinched and had to retrench. I have been looking for a favorable turn in the market any day, but none have showed. When this happened, I took the matter up with our three most important creditors, and after going over the situation, we decided to have an attachment proceed to save the assets from complete liquidation. E. D. Horkhemer, my brother, has made the financial arrangements with the new trustees. Under the cirucmstances, there were only two courses open for us. One would have been the easiest, but we chose assignments.”

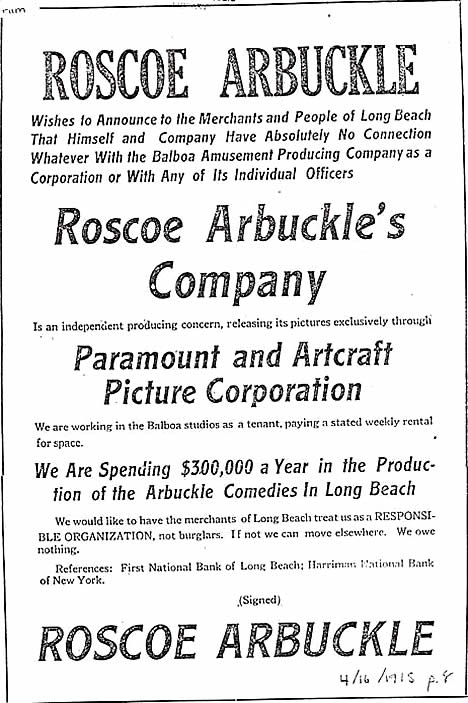

Arbuckle Disassociates Himself From Balboa

April 16: The Daily Telegram, p. 8: To disassociate himself from the bad rumors circulating about the Balboa Studios, Rosco “Fatty” Arbuckle put out this announcement below, and Arbuckle continued to use the Long Beach studio till July of that year, but in July, Fatty sought another location, leaving Long Beach and continuing his productions in Glendale at the Diando Studios where Baby Marie was producing her films..

April 20: The Moving Picture World: While Balboa is facing bankruptcy, three production companies are still filming there: 1) the Kathleen Clifford Co., finishing the nineteen episodes of Who Is Number One?; 2) Anita King Co.; 3) Mona Lisa Co. (films never completed).

Buster Keaton Leaves Comedy Team to Join Army

July 8: The Daily Telegram, “Buster Keaton Leaves Studio to Don U.S. Khaki: Popular LIttle Comedian Who Has Added Life to Arbuckle Comedies Leaves for Camp Kearny,” 7:4: The motion picture world lost one of its greatest comedians and America gained a splendid young soldier when Buster Keaton, the inimitable comic whose rare ability in the Fatty Arbuckle comedies won for him world-wide fame, departed for Camp Kearney this morning. His rise to screen fame has been as rapid as it is deserving and his début as a wearer of Uncle Sam’s khaki will be made in even a more earning manner.

[N.B.: The fact that this celebration was held in Seal Beach, a neighboring seaside town in Orange County, just south of Long Beach, is likely due to the fact that Long Beach was already a “dry” city even before the Prohibition. Theda Bara who had a house next door to Arbuckle on Ocean Boulevard, Long Beach would also frequent restaurants in Seal Beach, to be able to enjoy a glass of wine with her meals.]

July 8: The Daily Telegram (continued): In honor of Buster, his mentor and good friend, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, gave a farewell party at the Jewel City Café at Seal Beach last Saturday night. The entire Arbuckle company attended in addition to many outside friends. The party was not in any sense a “good bye” affair, but rather an attempt to show the honor and deep affection held for Buster Keaton. During the evening Mr. Arbuckle presented Buster with a token of esteem from himself and the company–a beautiful wallet containing a large sum of money. It is fitting that since the young screen comic has given up making us laugh to do his bit for this country that his success be recounted.

How Buster Entered the Movies

July 8: The Daily Telegram (continued): […] Less than two years ago Buster had no idea of entering motion pictures, but when Fatty Arbuckle left California for New York to produce comedies for the Comique Film Corporation releasing thru Paramount he needed a clever artist to work with Al St. John in support. It happened that Mr. Arbuckle’s general manager, Lou Anger, had been a well known vaudevillian. Having played on many bills with the three Keatons he knew the rare promise of Buster so he took Mr. Arbuckle to see the act. Upon seeing Buster in action the noted star decided immediately that in Buster there was the making of a leading picture comedian. In a short time Buster Keaton had signed a contract with Mr. Arbuckle and Joseph M. Schenck, president of the Comique Film Corporation. In the first comedy with Fatty the inimitable Buster scored a big hit. That comedy was The Butcher Boy, the first Arbuckle Paramount comedy produced. First, the professionals began to ask “Who is this boy?”–recognizing in him a coming star, and then the public became his following. With Al St. John and Alice Lake he furnished the sort of support that Fatty Arbuckle demanded in determination to produce the best comedies in the game. The results were that such newspapers and critics as the New York Times, the Winnipeg (Canada) Telegram and the Boston Evening Record devoted a column each to say that Fatty Arbuckle was making the best all-around comedies on the screen today. In each of these acknowledgements rich praise was given to Buster Keaton and Al St. John for their rare comic abilities.

Five Arbuckle/Keaton Films Made in New York and Six Made in Long Beach

July 8: The Daily Telegram (continued): In New York Buster played with Fatty in The Butcher Boy, The Rough House, His Wedding Night, Oh Doctor, and Fatty at Coney Island. Then, the rotund master of fun brot his company to Long Beach where they have been welcome citizens every since. My Country Hero, Out West, The Bell Boy, Moonshine, Good Night Nurse, and The Cook have been made in Long Beach.

To finish this last comedy which is a travesty of beach life the government granted Buster an extension of time. Last week the crowds on the beach were much amused with the antics of Fatty, Buster and Al–little knowing that it was hard to be funny facing the departure of a best friend and pal on a serious mission. Buster’s part in the comedy was finished Saturday and the party at Seal Beach came as a demi-tasse.

Guests at Buster’s Party in Seal Beach

July 8: The Daily Telegram (continued): Among those who paid honor to Buster were Lieut. Harry Spain and his wife from Camp Kearny. Lieut. Spain is an officer of Company C, 189th California Infantry–the company that Fatty Arbuckle adopted as “little brothers” two months ago. One of the most prominent comedy directors in motion pictures, Eddie Cline and his wife motored from Los Angeles to wish Buster God speed. The guests included Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, Lou Anger and his wife, Sophya Barnard; Al St. John and wife. Miss Alice Lake, Paul and Lilian Conlon, W. A. S. Douglas, president of the Diando Film Corp., and Miss Mildred Reardon; George Peters, Al Gilmore, Bert Ensminger, Fred Bagley, Glen Cavandar, Bobby Dunn, Ross Lewin, Lawrence Lewin, Dr. and Mrs. Maurice Kahn, Miss Considine, Eddie and Minnie Cline, Lieut. Harry Spain and wife and Richard Wise.

Entertainment at Buster’s Party

July 8: The Daily Telegram (continued): The comedy event of the evening was a minstrel show conducted by Fatty, Buster, Al, Eddie Cline and the Jewel City Entertainers–Mike Lyman, Hale Byers, Chris Schoenberg and Louie Stepp. Buster gave his famous snake dance assisted by Al St. John and Mike Lyman. A string of “hot dogs” served as the snake and Buster’s atttire consisted of a table cloth covering his clothes, and two napkins hanging from his ears.

No one said “good-bye” to Buster. It was just “so-long.” Needless to say where his thots were. His little mother and dad are in Muskegon, Mich., their home.

A Year Later: Arbuckle’s Dance–the Price for a Wet Party in a Dry City

December 21: The Daily Telegram, “To Recover Bond From Balboa Men,” 16:4: The city of Long Beach is attempting to recover from H. M Horkheimer, who was president of the erstwhile Balboa Amusements Producing Company, and R. R. Rockett, another moving picture man, the $100 bail bond which was given by them for A. C. Thomas, arrested Novemer 28, 1917, at the Balboa studios on a charge of giving away alcoholic drinks.

Since the financial collapse of the Balboa company, Mr. Horkheimer has made his residence in New York, it is understood, so his case will offer some obstacles to the Long Beach authorities. Mr. Rockett, once associated with the Balboa company, according to police information is now at Universal City, in the employ of the Universal Film company.

The Balboa company entertained on the night of November 28, 1917, and the flowing bowl was much in evidence when Chief of Police C. C. Cole and a squad of officers raided the studios, it is alleged. Thomas was arrested as the dispenser of drinks.

The police records show that Thomas failed to appear for trial originally and that Judge C. V. Hawkins declared the bail forfeited. It is alleged by the city that they then found the bond worthless and brot Thomas into court with a bench warrant. He was found guilty in the police court on May 16, 1918, and paid a fine of $100 on May 23.

Acts of God: Closing the Horkheimer Chapter

The Great War

The havoc generated by the Great War resulted in immeasurable material damage, economic paralysis, and the enormous loss of human life, the war scattering in its wake millions of disillusioned souls. All the countries, winners and losers alike, suffered terribly. In its scope and totality, the Great War (World War I) ushered in a violent age of international warfare, ironically, at the inception of an emerging millennium of global expansion and interdependence. Never before had a war exhausted so many human and material resources among the richest nations of the world. Europe bled itself dry, scarring both the psyche and the face of Europe. The number of casualties in previous wars had no equal to the almost 9,000,000 servicemen who perished in the combined armed forces of the Allied and Associated powers as well as the Central Powers. Besides the terrible loss of soldiers, the direct war expenditure of the Allied and Associated Powers totaled approximately $145,400,000,000, including as well British, French, and U.S. loans of around $20,000,000,000 to other fighting countries. For the Central Powers the cost totaled around $63,000,000,000, with German loans of $2,400,000,000. Farms, villages, factories and homes turned to dust in the most industrialized departments of France, where most of the war was fought, effacing the signs of the region’s former prosperity.

Pandemic

As if the Great War had not done enough to depress the war-weary populations, an unusually potent virus would end up killing more American soldiers than those who had died in combat in all American wars combined. Studies by Dr. Jeffrey K. Taubenberger and his research team recently furnished the first direct evidence on the genetic makeup of the 1918 virus, determining that the killer virus developed along normal channels, with nothing aberrant about its origin. As yet another roadblock, this epidemic came on scene when the Horkheimers were still expecting an upswing in the market. Until the research by Dr. Taubenberger and his team, there had only been indirect clues about the nature of the virulent virus. Firstly, viruses were unknown in 1918, so scientists had to depend on antibody patterns among survivors of the epidemic, but antibodies give incomplete data about any virus. Lung tissue preserved in formaldehyde, from U.S. soldiers who fell victim to the disease, were studied at the Armed Forces Institute. Research by Dr. Taubenberger was able to piece together parts of five different genes from the killer strain, less than 10 percent of the entire genome.

The influenza epidemic climaxed in September 1918. In October 1918, it would reach Long Beach. In September 1918, the influenza struck a military camp outside of Boston. Many of the soldiers fell instantly and gravely ill, turning blue, bleeding from the nose, dying within 48 hours. In one day 90 soldiers died. The epidemic entered Southern California via an infected ship in the harbor of San Pedro, next to the port of Long Beach. On October 11 1918, all schools, theatres, and public meeting places were closed throughout the county of Los Angeles. In Long Beach, January 8, 1919, a new flu ban was imposed against public assemblies at high school football games and sporting events. On January 21, 1919, Long Beach proclaimed a discontinuance of all public gatherings. By January 23, 1919, theatres in Long Beach were to close on account of the influenza, all the restrictions finally being lifted by January 31, 1919. Despite all the precautions, the influenza spread like wild fire, as described by Claudine Burnett:

In the first 2 weeks of October between 400 and 500 cases had been reported in Long Beach and 5 deaths had occurred. Before it was over in February of 1919, there were 148 deaths of the flu in Long Beach (compared to 60 Long Beach lads who lost their lives in World War I). In the United States alone more people died of the flu (550,000) in 1918 than the U.S. military lost to combat in both World Wars, Korea and Vietnam. (“Influenza Ghost”)

Years later, it was explained that the influenza had probably started on a pig farm in Iowa. According to Claudine Burnett, after the annual Iowa Cedar Rapids Swine Show in September 1917, millions of pigs fell ill and thousands died. The virus first spread among animals—moose, elk, bison, and sheep, before reaching the human population in North America. Doctors failed to acknowledge the epidemic until American troops transported the dreaded disease to an already-devastated Europe.

The movie industry too experienced a shutdown due to the flu. On November 15, 1918, four days after the Armistice was signed, ending the Great War, Variety printed an article, entitled, “Industry Resumes Releasing After Five Weeks’ Shutdown.” Once again, the Horkheimers would not experience an upswing in the market due yet to another catastrophe. It would take at least a year for the industry to recover from the paralysis caused by the influenza epidemic:

The exchanges throughout the country where the epidemic closed down the theatres were also shut down and the incomes of the producing and distributing companies was cut to almost nothing because of the countrywide closing of the houses. It was a tremendous blow to the industry and those that are at its head say that it will be at least a year before the companies can recover from the body blow that it has received.

Oil Gushers Galore

As if world war and a global epidemic were not enough to discourage the Horkheimers’ return to filmmaking, another unexpected discovery altered physically and economically the city of Long Beach, transforming it from an entertainment and resort town to a world-class port and industrial center. In 1921, the world’s richest deposit, in terms of barrels of crude oil per acre, gushed out of Signal Hill, at that time a part of Long Beach. Within the first fifty years of drilling 2,400 wells, over 859,000,000 barrels of petroleum were extracted in Signal Hill and the Long Beach area. The new darling of Long Beach was petroleum, not celluloid, with the city going gaga over the revenues generated by the plentiful natural resource.

Though the movie industry would continue to produce films in Long Beach till1922, gone were the days when Balboa would be counted among the major film plants of Hollywood, and no longer would Balboa represent the biggest employer and greatest tourist attraction in Long Beach. Oil money would drench the city and steal the show. In a few more years, the studio site would shrink in size, as real estate development closed in, and the final coup de grâce would be delivered in January 1925, with the demolition of the famous glassed-in stage and its surrounding buildings. At that point in time, the Balboa Amusement Producing Company became history.