California Indian Conference 2020 Digital Exhibition

https://cic.library.fresnostate.edu/exhibition/

50th Annual Pow Wow, Postponed until Further Notice!

The CSULB Pow Wow originally scheduled for March 14 & 15 2020 has been postponed until further notice. Come join us for the 50th Annual CSULB Pow Wow at Puvungna. The largest and oldest student sponsored event on campus, our celebration of life is attended by the CSULB American Indian community, alumni, staff, students, faculty, the general public, dancers, singers and venders who make up the over six-thousand people who attend our annual celebration of Native American Culture at “the Beach.” Held at the upper campus quad, the event is free however parking is $10 per day. To learn more about the 50th Annual Pow Wow click on this link and the links in the column to the right to see past Pow Wows at the Beach.

Debut of Virtual Reality experience of the Birth of the Tongva People

BIRTHPLACE OF THE PEOPLE

A 14 minute 360/VR experience that illustrates the birth of the Tongva People on the site of Puvungna- what is now the CSULB campus. This one-of-a-kind experience created by students and faculty in the Anthropology Department, will be featured in the “Igloo” Cylindrical VR Theater, located in the CSULB Library’s

Gerald M. Kline Innovation Space.

The film will run continuously between 12pm and 2pm, with each viewing accommodating 20 viewers.

WORLD ANTHROPOLOGY DAY | FEBRUARY 20TH, 2020

Roundtable discussions with Scott Wilson (Anthropology), Cindy Alvitre (American Indian Studies) and Carly Lake (Artist) will take place at 12:30pm and 1:30pm, in the room adjacent to the Innovation Space.

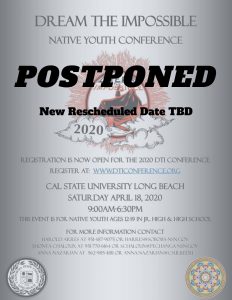

Dream the Impossible Native Youth Conference April, 2020

CSULB will host the 14th Annual Dream the Impossible Native American Youth Conference on has been postponed!

For details see: http://dticonference.org.

http://dticonference.org./

49th Annual Pow Wow

Celebrating 50 Years of American Indian Studies at CSULB.

Rain or Shine, the CSULB American Indian community, alumni, staff, students, faculty and the general public who make up the six-thousand visitors who attend our annual celebration of Native American Culture at “the Beach” this year on March 9 & 10, 2019 at the 49th Long Beach Pow Wow at Puvungna.

To learn more about the Annual Pow Wow check out the links on the right column of the AIS Main Page and the following link. Link to Pow Wow Information

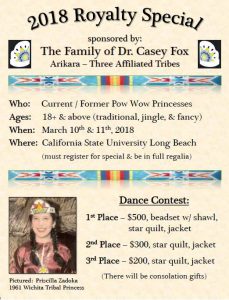

48th Annual Pow Wow Rain or Shine

Rain or Shine, the CSULB American Indian community, alumni, staff, students, faculty and the general public who make up the six-thousand visitors who attend our annual celebration of Native American Culture at “the Beach” this year on March 10 & 11, 2018 at the 49th Long Beach Pow Wow at Puvungna.

To learn more about the Annual Pow Wow check out the links on the right column of the AIS Main Page and the following link. Link to Pow Wow Information

Hock E Aye VI Edgar Heap of Birds

The American Indian Studies Program and the School of Art is pleased to present a Reception for Edgar Heap of Birds on February 8, 2018, in USU-310 at 5:00 pm, followed by a Presentation in Lecture Hall 150 at 7:00 PM. His new exhibition, Do Not Dance For Pay opens on February 10, 2018.

The American Indian Studies Program and the School of Art is pleased to present a Reception for Edgar Heap of Birds on February 8, 2018, in USU-310 at 5:00 pm, followed by a Presentation in Lecture Hall 150 at 7:00 PM. His new exhibition, Do Not Dance For Pay opens on February 10, 2018.

Click link for information about Reception and Lecture : heap of birds flyer

See below for information about Exhibition:

Garis & Hahn presents Do Not Dance For Pay

Hock E Aye VI Edgar Heap of Birds

February 10 – March 10, 2018

Opening Reception: February 10th | 5-8pm

January 25, 2018 (Los Angeles, CA) Garis & Hahn is pleased to present Do Not Dance for Pay,

a survey of work by the renowned multi-disciplinary Cheyenne and Arapaho artist, Hock E Aye

VI Edgar Heap of Birds. Featuring works from six distinct series made over four decades, the

exhibition marks Heap of Birds’ first Los Angeles show in ten years. The title of the exhibition

alludes to indigenous art and its deep-rooted link to tourism and an art market that has been

historically driven by the non-Native. Most artists “dance for pay”, a reference to the making of

apolitical art with the focus on commercial sales–not so with the work of Heap of Birds. This

survey is the artist’s inaugural exhibition with the gallery and will be on view February 10

through March 10, 2018.

In recent years the post-war art historical narrative has been revised, with artists of color, longexcluded

from contemporary art history, finally finding agency for their work. Enter Edgar Heap

of Birds, who was featured on the cover of the October 2017 issue of Art In America.

Throughout his singular four-decade career, Heap of Birds has brandished words as weapons.

The words and phrases he scrawls on his paintings and monoprints act as scathing indictments

of the odious history of appropriation and violence against indigenous people. His words serve

as an effectual counterweight to the biased historical narratives regarding the Native presence.

Through public art pieces, biting political text-based work, poetry, large-scale drawings,

monoprints, signs, and more intimate abstract paintings, Heap of Birds purposefully subverts the

power dynamics between the privileged and the marginalized, conventional society and the

reservation. His multifaceted oeuvre rejects the separation between protest and poetry, taking

aim at a history which obscures the Native population. For his “Native Hosts” series (begun in

the late 1980s), Heap of Birds manipulates institutional regulatory signs which he then installs in

outdoor public spaces. He repurposes these ubiquitous place markers, identifying the tribes that

lived there prior to colonization, explicitly asserting the historical sovereignty of Native nations.

Displacing the authority of the state by printing the official name of the site backwards, these

slyly subversive works remind the public of an unpleasant history, subtly positioning the Native

world in ascendance.

Heap of Birds’ series of monoprints, including “Secrets of Life and Death” and “Dead Indian

Stories”, are text-based works, which express brutal truths about the subjugation of Native

Americans in the United States. Other pieces are more personal, proffering reflections of his

own subjective Native experience. Relatedly, the continuing “Neuf” series of abstract paintings

are derived from his experiential memories of the landscape of the Cheyenne and Arapaho

Reservation.

Heap of Birds roots his practice in Cheyenne spirituality and the indigenous way of seeing and

being in the world. He asks critical questions about history and identity, time and modernity,

social justice and personal freedom, power and the value of contemporary art in today’s society-

-questions he’s been asking for decades that currently lie at the center of our national debate.

He has compared his art to “sharp rocks”, i.e. arrow heads of the past, an apt metaphor for his

excoriating critiques regarding the loss of autonomy for the Native American. Focusing on the

survival of Native peoples in contemporary society, Heap of Birds intends to honor indigenous

citizens of ancient and contemporary communities, while inviting the non-Native public to gain a

broader cultural and historical understanding.

About Hock E Aye VI Edgar Heap of Birds

Heap of Birds received his Master of Fine Arts from Tyler School of Art, Temple University

(1979) and was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts Degree from the Massachusetts

College of Art and Design, (2008). The artist has exhibited his works at The Museum of Modern

Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, National Museum of the American Indian, New York, NY;

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada;

Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia; Documenta, Kassel, Germany; University Art

Museum, Berkeley, California; Association for Visual Arts Museum, Cape Town, South Africa;

Hong Kong Art Center, China; Grand Palais, Paris, France; and the 52nd Venice Biennale, Italy

as part of the Smithsonian’s entry.

About Garis & Hahn

Garis & Hahn is a gallery-cum-Kunsthalle that mounts exhibitions focused on conceptual

narratives and relevant conversations in contemporary art. By displaying an array of carefully

curated artists, the gallery endeavors to provide accessibility, education, awareness, and a

market to the art while engaging both the arts community and a broader general audience.

Gallery Hours:

Tuesday – Saturday, 12 – 6pm

Contact Information:

1820 Industrial Street Los Angeles, CA 90021

(P) 213.267.0229 | (E) info@garisandhahn.com

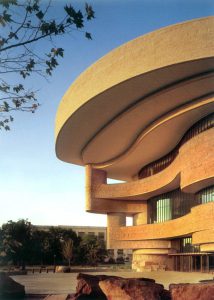

Indigenous Design: Emerging Gifts — A Presentation by Renown Indigenous Architect Johnpaul Jones

47th Annual Pow Wow

Thank you to everyone who joined us at our annual Celebration of life, the 47th Annual Pow Wow at Puvungna. We are feeling very grateful for the continued support for the largest and one of the oldest students sponsored events at CSULB that took place on March 11 & 12.

Thank you to everyone who joined us at our annual Celebration of life, the 47th Annual Pow Wow at Puvungna. We are feeling very grateful for the continued support for the largest and one of the oldest students sponsored events at CSULB that took place on March 11 & 12.

Save the Date: Mark your calendars to join the CSULB American Indian community, alumni, staff, students, faculty and the general public who make up the six-thousand visitors who attend our annual celebration of Native American Culture at “the Beach” next year on March 10 & 11, 2018 at the 48th Long Beach Pow Wow at Puvungna.

A special thanks to our student volunteers who had us set up in record time. Students who were interested in learning more about the meaning and significance of Pow Wow were able to enroll in a new one-unit course designed specifically for Pow Wow volunteers. This Art 490 Special Topics course and other three-unit AIS courses, allowed students to attend Pow Wow volunteer workshops and also earn course credit to volunteer at the Annual Pow Wow.

To learn more about the Annual Pow Wow check out the links on the AIS Main Page and the following link. Information about Pow Wow

California Indian Genocide Awareness

As part of an ongoing effort to increase awareness of the Californian Indian Genocide, the American Indian Studies Program and the American Indian Student Council sponsored several events this Fall of 2016.

The American Indian Student Council installed two public artworks to raise awareness of the California Indian Genocide on campus that was on view for the entire month of November. Link to article These artworks installed by American Indian Student Council officers, Ashley Glenesk and Miztla Aguilera with Professor Craig Stone were seen by thousands of students, faculty and staff were also featured on the CSULB webpage. Link to article

As part of Native American Month, the Native American Student Council sponsored a lecture by Benjamin Madley the author of An American Genocide: The California Indian Catastrophe 1846-1873, in conjunction with the Ethnic Studies 319 and AIS 336 courses. The presentation took place in the USU Ballrooms on Tuesday, November 8th from 2:00 to 3:15 pm, followed by a book signing. Over one-hundred and fifty students attended the lecture in conjunction with the Puvu Indigenous Cultural Sustainability Lecture Series and the Scholarly Intersections Grants from the College of Liberal Arts.

It’s time to acknowledge the genocide of California’s Indians

By Benjamin Madley

Between 1846 and 1870, California’s Indian population plunged from perhaps 150,000 to 30,000. Diseases, dislocation and starvation caused many of these deaths, but the near-annihilation of the California Indians was not the unavoidable result of two civilizations coming into contact for the first time. It was genocide, sanctioned and facilitated by California officials.

Neither the U.S. government nor the state of California has acknowledged that the California Indian catastrophe fits the two-part legal definition of genocide set forth by the United Nations Genocide Convention in 1948. According to the convention, perpetrators must first demonstrate their “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such.” Second, they must commit one of the five genocidal acts listed in the convention: “Killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

It is not an exaggeration to say that California legislators also established a state-sponsored killing machine.

California’s Legislature first convened in 1850, and one of its initial orders of business was banning all Indians from voting, barring those with “one-half of Indian blood” or more from giving evidence for or against whites in criminal cases, and denying Indians the right to serve as jurors. California legislators later banned Indians from serving as attorneys. In combination, these laws largely shut Indians out of participation in and protection by the state legal system. This amounted to a virtual grant of impunity to those who attacked them.

That same year, state legislators endorsed unfree Indian labor by legalizing white custody of Indian minors and Indian prisoner leasing. In 1860, they extended the 1850 act to legalize “indenture” of “any Indian.” These laws triggered a boom in violent kidnappings while separating men and women during peak reproductive years, both of which accelerated the decline of the California Indian population. Some Indians were treated as disposable laborers. One lawyer recalled: “Los Angeles had its slave mart [and] thousands of honest, useful people were absolutely destroyed in this way.” Between 1850 and 1870, L.A.’s Indian population fell from 3,693 to 219.

It is not an exaggeration to say that California legislators also established a state-sponsored killing machine. California governors called out or authorized no fewer than 24 state militia expeditions between 1850 and 1861, which killed at least 1,340 California Indians. State legislators also passed three bills in the 1850s that raised up to $1.51 million to fund these operations — a great deal of money at the time — for past and future anti-Indian militia operations. By demonstrating that the state would not punish Indian killers, but instead reward them, militia expeditions helped inspire vigilantes to kill at least 6,460 California Indians between 1846 and 1873.

The U.S. Army and their auxiliaries also killed at least 1,680 California Indians between 1846 and 1873. Meanwhile, in 1852, state politicians and U.S. senators stopped the establishment of permanent federal reservations in California, thus denying California Indians land while exposing them to danger.

State endorsement of genocide was only thinly veiled. In 1851, California Gov. Peter Burnett declared that “a war of extermination will continue to be waged … until the Indian race becomes extinct.” In 1852, U.S. Sen. John Weller — who became California’s governor in 1858 — went further. He told his colleagues in the Senate that California Indians “will be exterminated before the onward march of the white man,” arguing that “the interest of the white man demands their extinction.”

Beyond premeditated, systematic killings of California Indians, other acts of genocide proliferated too. Many rapes and beatings occurred, and these meet the U.N. Genocide Convention’s definition of “causing serious bodily harm” to victims on the basis of their group identity and with the intent to destroy the group. The sustained military and civilian policy of demolishing California Indian villages and their food stores while driving Indians into inhospitable mountain regions amounted to “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.” Because malnutrition and exposure predictably lowered the birthrate, some state and federal decision-makers also appear guilty of “imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.”

Finally, the state of California, slave raiders and federal officials were all involved in “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” Thousands of California Indian children suffered such forced transfers. By breaking up families and communities, forced removals constituted “imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.” In effect, the state legalized abduction and enslavement of Indian minors; slavers exploited indenture laws and federal officials prevented U.S. Army intervention to protect the victims.

The issue of genocide in California poses explosive political, economic and educational questions for the state, California’s tribes and individual California Indians. It is up to them — not academics like me — to determine the best way forward.

Will state officials tender public apologies, as Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush did in the 1980s for the relocation and internment of some 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II? Should state officials offer compensation, along the lines of the more than $1.6 billion Congress paid to 82,210 of these Japanese Americans and their heirs? Might California officials decrease or altogether eliminate their cut of California Indians’ annual gaming revenues ($7.3 billion in 2014) as a way of paying reparations? Should the state return control to California Indian communities of state lands where genocidal events took place? Should the state stop commemorating the supporters and perpetrators of this genocide, including Burnett, Kit Carson and John C. Frémont? Will the genocide against California Indians join the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust in public school curricula and public discourse?

These are crucial questions. What’s beyond doubt is that the state and the federal government should acknowledge the genocide that took place in California.

Decency demands that even long after the deaths of the victims, we preserve the truth of what befell them, so that their memory can be honored and the repetition of similar crimes deterred. Justice demands that even long after the perpetrators have vanished, we document the crimes that they and their advocates have too often concealed or denied. Finally, historical veracity demands that we acknowledge this state-sponsored catastrophe in all its varied aspects and causes, in order to better understand formative events in both California Indian and California state history.

Benjamin Madley is assistant professor of history at UCLA and the author of “An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873.”

Link to Past Genocide Awareness Efforts